CNT Synthesis

Carbon Nanotubes (CNTs) possess exceptional electrical, mechanical, thermal and optical properties. These properties have enabled a vast array of applications across multiple disciplines of science and technology. However adoption of many of these technologies has been slow due to the difficulty of producing large amounts of high quality CNTs. Improvements in CNT synthesis technology promise not only to make many of these applications cost-effective, but also to provide a potential method for fixating carbon derived from natural gas or biogas in an economically valuable form.

The Pasquali lab is currently studying floating catalyst chemical vapor deposition (FCCVD) synthesis of CNTs from methane. Our primary goal is to develop an efficient, scalable FCCVD process to convert methane into high-quality CNTs and hydrogen. Like many other catalytic processes, the FCCVD process for CNTs synthesis involves physical and chemical phenomena that unfold across multiple time and length scales. As such, in order to achieve a complete understanding of the reaction working mechanisms, the synthesis team heavily relies on chemical reaction engineering principles to decouple all these intertwined phenomena.

Atomic scale phenomena

Methane thermal decomposition

Hydrocarbons are unstable when exposed to high temperatures and tend to thermally decompose. Methane, the hydrogen richest hydrocarbon, is not an exception. Despite the thermodynamic instability of methane would suggest the possibility to break down the molecule at temperatures above °C, our reactors require temperatures close to 1200°C to achieve relevant methane decomposition rates, owing to the hydrogen rich environment and to the exceptionally high CH3-H bond energy. The decomposition proceeds according to a well studied radical mechanism, providing the chemical species active towards CNTs synthesis.

Catalyst nanoparticles evolution

Once the catalyst precursor is decomposed to provide gaseous atomic iron, metallic nanoparticles are formed by nucleation and the aerosol of nanoparticles subsequently evolves (in size and concentration) following the General Dynamic Equation (GDE).

Carbon nanotubes nucleation and growth

The active species formed by methane thermal decomposition are ready to decompose on the surface of newly generate catalytic floating particles. The particles act as a sink of carbon, sequestrating carbon atoms from the gas phase, to form solid nanotubes with a mechanism resembling the Ziegler-Natta polymerization of propylene.

Reactor scale phenomena

Energy, mass and momentum transport

At the reactor scale, the transfer of energy, mass, and momentum governs the temperature, species concentrations, and flow fields, which are critical for creating the local conditions necessary for the atomic-scale phenomena to proceed effectively. Within the continuum regime, computational fluid dynamics simulations, when properly supported with experimental data, can characterize these fields and establish a combined experimental–computational feedback loop that enhances our understanding of the reaction environment.

Mixing all the ingredients, we can observe the result of their interplay from our window to the reactor…

CNT fiber spinning

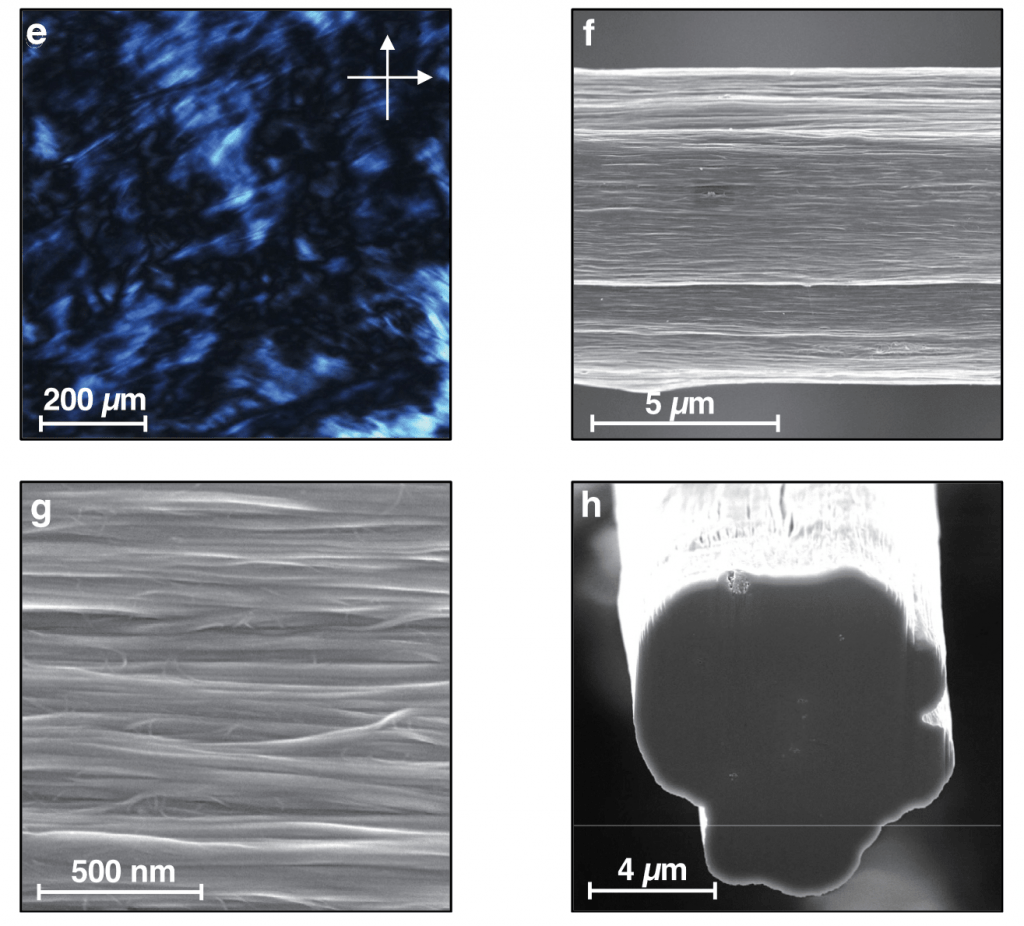

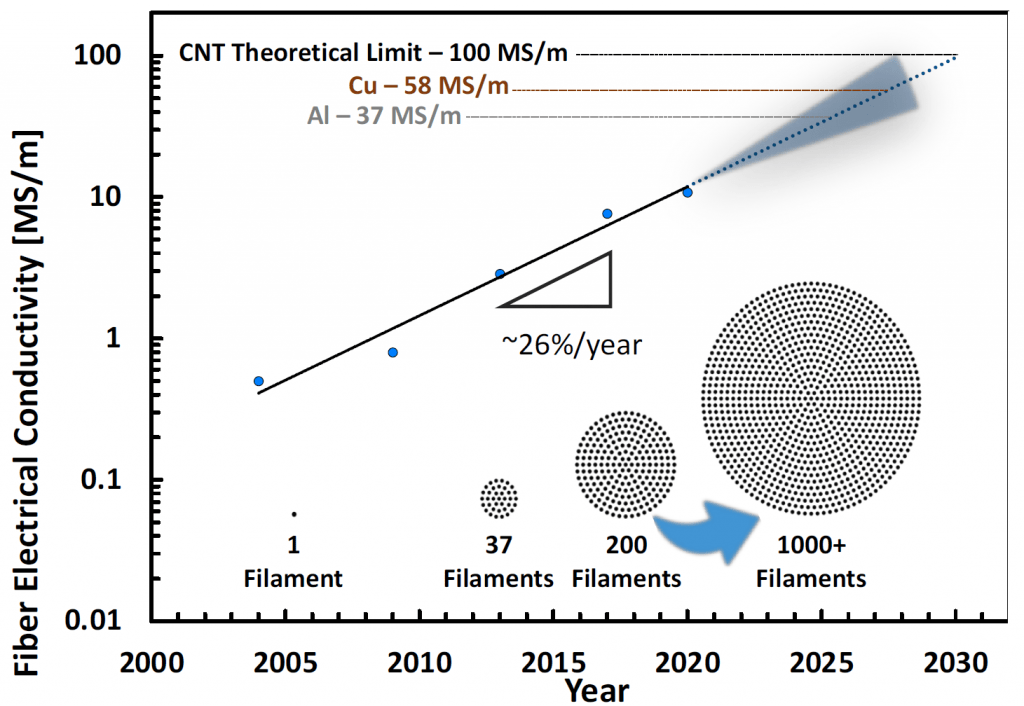

High-performance carbon nanotube (CNT) materials such as fibers and films can displace steel and other metals (e.g., aluminum, copper, and iron) – major offenders in terms of energy consumption and CO2 footprint – in a broad range of applications. The Pasquali Lab at Rice University is a world leader in technologies underlying CNT fiber spinning, a method similar to that used for the production of polyethylene (Dyneema and Spectra) and aramid (Kevlar and Twaron) fibers, as well as the precursors of carbon fibers. CNT fiber spinning is particularly attractive because it decouples fiber production from CNT synthesis and can deliver high-quality fibers at scale.

A recent article by the Pasquali group reported on the latest properties of solution-spun CNT fibers with a tensile strength of 4.2 GPa (specific strength of 2.1 N/tex, or ~55% of IM10 carbon fiber) and electrical conductivity of 10.9 MS/m (specific conductivity of 5640 S.m2/kg, or ~85% of copper). The incorporation of such high-performance CNT fibers into products is particularly appealing for applications where materials need to combine outstanding properties with light weight and flexibility, like those often encountered in the aerospace, automotive, electronics, robotics, power transmission, biomedical, and telecommunications industries. However, the ultimate adoption and incorporation of CNT materials into products and applications will require large-scale production at lower cost, higher efficiency, and strategies for managing their end-of-life. Current research efforts focus on improving both the scalability and sustainability of CNT fiber production. Examples include studies of alternative combinations of solvent/coagulant for CNT solutions, CNT materials produced from mixtures of CNTs synthesized by different methods, and recycling of CNT materials with predictable properties.

Boron Nitride Nanotubes (BNNTs)

Structural analogs of CNTs, boron nitride nanotubes (BNNTs) share many of the favorable properties of CNTs (e.g., low density, high strength, high thermal conductivity) with some key differences. Unlike CNTs, BNNTs are neutron shielding, electrically insulating, and stable in air up to 900 °C. This unique combination of properties makes BNNTs perfect candidates for the demanding conditions found in aerospace, where material integrity at extreme high and low temperatures is critical.

The Pasquali lab is currently researching BNNT purification, BNNT liquid crystal formation, and adapting existing wet spinning techniques for the production of macroscopic BNNT materials, like thin films and fibers. With a delay of ~20 years relative to research on CNTs, we are now seeing the solution-processed neat BNNT materials become a reality. The vision of high-performance BNNT materials will soon be attainable if BNNTs continue to follow the pace of development set by CNTs.